Shinnecock Artist Visits Eastern

November 21, 2021

Colonialism is often thought of as a historical incident something of the past. But discrimination towards indigenous peoples today stems directly from those past injustices.

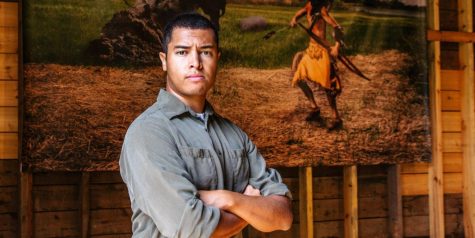

Over the semester Alpha Eta Psi (PTK Chapter of the Eastern Campus) had the privilege of interviewing Jeremy Dennis, a tribal member of The Shinnecock Nation and contemporary fine art photographer.

The Shinnecock Nation is a self-governed Native American tribe located on the southeastern end of Long Island, about 20 miles from SCCC’s Eastern Campus. They gained federal recognition in 2010 and are made up of over 1200 members today.

We sought to connect with members from local Native American communities for our HIA (Honors in Action) research project, recognizing the importance of indigenous people telling their own stories.

Jeremy Dennis uses photography to shed light on injustices that need to be talked about. “I like to focus on issues of colonization and assimilation, how Shinnecock has been treated historically and just telling those truths,” Dennis says. “If you do it through the arts people will really engage with it and spend their own time learning from it.”

Growing up, Dennis was surrounded by many mentors and artists including his mother and uncle, who influenced him and his career path. Dennis’s mother went on to become a visual art teacher and did not have the opportunity to use photography how she wished. “At that time, a lot of people who determined the future of visual artists, like curators and gallerists, turned away Native Americans who didn’t work in craft. Or they turned away women artists en masse because of the trends and what they believed were artists who should be valued,” said Dennis. His uncle, Herbert Randall, who was able to use photography as means to tell truths, participated and photographed the Freedom Summer in Mississippi, 1964.

PTK intends to be a proponent of awareness. The Shinnecock Nation and other Indigenous communities across the country are hurting, and it is because the effects of colonialism are ongoing. A pattern of prejudicial attitudes and policies can be traced back to the first settler-colonists.

This pattern is observed in one of our own communities on Long Island. “Shinnecock in Southampton, NY, faces issues of historical land theft from Southampton Town that we are still trying to regain. We face economic disadvantages, homelessness, and economic development conflicts with our neighbors. We also face issues of prejudice and discrimination. Some people fail to acknowledge our continued presence and sovereignty, and others say we are not ‘Indian’ enough based on our appearance – but Native people are the only group that faces that false criticism. Today we have the issue of overcoming COVID-19,” Dennis explains.

Many non-native people have adopted an ignorant mindset in how they perceive indigenous communities, heritage, and identities. Harmful attitudes argue that “the past is in the past” and find uncomfortableness in the part of indigenous identity that is made up of their people’s oppression.

“We need to have difficult conversations and acknowledge darker history to try to make positive change,” Dennis says. “We all have a stake in these issues and are connected.”

Although they are constantly facing disadvantages, The Shinnecock Nation continues to exhibit fortitude and resilience against the disparities they have inherited. “Shinnecock, as an Indigenous Community and the other thirteen communities here on Long Island who are native, we’ve been here for more than 10,000 years,” Dennis says.

One example of resilience is observed in the up-and-coming BIPOC (Black, indigenous, people of color) art space called Ma’s House. Ma’s House belonged to Dennis’s grandmother Loretta Silva, or her native name Princess Silva Arrow. “With COVID, and all the social distancing, and all the canceled opportunities for myself as an artist I had the idea of trying to restore this house,” Dennis says Ma’s House is a fitting name for a place that welcomes guests before they step through the front door. Dennis describes Ma’s House as “a beloved family home and space of so many memories and community gathering.”

Ma’s House is not a traditional museum. It fosters community with its guest artists through a residency program, where artists can live, create and display their pieces. Dennis emphasizes the critical role that art can play when uniting people that are so unalike from each other. “I really hope that art will be the main focus. On the East End, we’re such a segregated people,” he says. “So art is one of those avenues that you can just put whatever is on your mind out there, you can bring people together to enjoy that art, and you don’t have to turn people away because, in some sense, everyone loves art. Everyone can appreciate art no matter what the content is.”

Honoring the distinctness of a unique community like the Shinnecock Nation allows indigenous people to retain their culture and togetherness. At the same time, tribal members like Jeremy Dennis recognize the importance of making community-to-community connections.

Those looking to support the Shinnecock Nation can do so in a multitude of ways, from visiting community spaces such as Ma’s House or attending the Shinnecock Nation’s annual Powwow, which is one of their most important fundraisers and has not been organized in the last two years due to COVID-19.

“The Powwow grounds are pretty much the heart of the reservation,” Dennis says. The Powwow sales go towards things like scholarships and social programs and also fund everyday necessities such as filling in potholes.

Support can also be provided by staying educated and fostering knowledge about the issues that Native American communities face across the country, issues that they have inherited from colonialism. Asking questions like “Whose land do I occupy?” is a good start.